Sunday, April 30, 2017

Friday, April 28, 2017

An Interview With Dana King

Although Dana and I have not quite met, we have known each other for years on Facebook and on online blogs. Right from the start, his stories impressed me along with his thoughtful blog and our interchanges on Facebook. GRIND JOINT was a favorite of mine a few years back. We catch up with him a few books later here.

Let's start with an elevator pitch of RESURRECTION MALL.

Let's start with an elevator pitch of RESURRECTION MALL.

Televangelist Christian Love has outgrown his church and

studio in Pittsburgh. He sees an opportunity to expand his footprint by converting

an abandoned shopping center into Resurrection Mall, a facility that caters to

religious-themed businesses, with his expanded church and broadcasting facility

as the anchor. What he doesn’t take into account is Res Mall is near the center

of Penns River’s burgeoning drug trade, where having the Lord on your side isn’t

as helpful as one would hope.

1. Did you always plan to write?

Nope. My dream was to play trumpet in a symphony orchestra.

Got a Master’s in Music and everything. There was a catch. Remember those ads

for the pro golf tour? These guys are

good? Well, those trumpet players are really

good.

2. Do you have a writing routine or do you approach it

differently day to day?

I’m very much a routine writer. On work days I write every

evening after supper. On days off I get in a couple of hours mid-afternoon,

with a set amount of work I have to complete each day. If I miss a day I have

to make it up.

3. Do you have a first reader?

I have a first listener. I read each chapter to The Beloved

Spouse as it’s finished, both first and last drafts.

4. Do your ideas for novels start with character, story,

setting or something else?

All the ideas for Penns River novels have to be something I

can reasonably make happen in the town. How the story progresses and shakes out

will have a lot to do with the nature of the characters, but the town comes

first.

5. What writers have influenced your writing the most?

Elmore Leonard and Ed McBain early and always. The others

have shifted. I see more Joe Wambaugh in my work all the time. I can’t say

James M. Cain’s writing has influenced me, but there’s a quote of his I love

and try to keep in mind, especially in the Penns River books. (“I make no conscious effort to be tough, or

hardboiled, or grim, or any of the things I am usually called. I merely try to

write as the character would write, and I never forget that the average man,

from the fields, the streets, the bars, the offices and even the gutters of his

country, has acquired a vividness of speech that goes beyond anything I could

invent, and that if I stick to this heritage, this logos of the American

countryside, I shall attain a maximum of effectiveness with very little effort.”)

There’s a draft in each book where I work on nothing but getting that voice

right. Yes, I know Cain said, “with very little effort.” I ain’t James M. Cain.

6. What do you see as your greatest strength and greatest

weakness as a writer?

I think my greatest strength is that I’ve learned how to

take advantage of what I do well, and to minimize—hide, even—what I’m not as

good at. My books are dialog heavy mainly because I’m comfortable writing

dialog. I think my musical training helped me develop an ear where I can read a

passage aloud and just know if it sounds right.

My greatest weakness is a lack of creative spontaneity. I’m

not good at thinking up what happens next while sitting at the keyboard. I’ve

learned to minimize that by adopting what Charlie Stella calls a “documentary”

style. I make rough outlines so I know what has to happen in each scene, then

describe it as if it has already taken place.

7. Is Penn's River a real place?

Yes and no. There are three small towns nestled together on

the banks of the Allegheny River about twenty miles from Pittsburgh that are

Penns River for all intents and purposes. I make things up as I need them, but

I’m so closely tied there I use real maps when coming up with street names and

describing directions. Many, maybe most, of the locations I use are real places

and I look for excuses to drop them in. For example, if two characters meet for

lunch, they’ll go to an actual local restaurant. Of course, if a business is a

crime scene or front for a criminal enterprise, I make those up. I’m looking

for local flavor, not lawsuits.

8. You have two series now, how are they different? How do

you decide what plot idea fits each? Have you ever switched a story idea from

one series to the other?

The differences go back to an earlier question, about my

ideas. Penns River stories have to suit the town. Nick Forte stories have to

suit Forte. Resurrection Mall is the

perfect example. I originally planned and outlined it as a Forte story. I even

wrote 40,000 words before I realized it wasn’t going anywhere, outline or not.

I took a week off to think about it and realized the problem was the story belonged

in Penns River. So I started over from scratch, except for the title and the

idea of a religious-themed shopping center. The only things I re-used were the

minister’s name (Christian Love), and the tag line for his new mall planned for

the site of an old one (“Raised, not razed.”)

Another difference is the Forte stories are in first person

and are very much character studies of Forte’s increasingly dark life and world

view. Characters in Penns River aren’t as introspective.

Speaking of ideas, I’d like to interject a quick side note.

A lot of writers complain when readers ask where they get their ideas. (I’ve

even heard of readers who don’t like the question from other readers. Go

figure.) I love when people ask where I get my ideas. Readers sometimes think

there’s a wall between them and authors, and that an ability to come up with good

ideas is the ladder we climbed to get over it. That’s not at all true—all of us

are tripping over ideas; the trick is which ones we can write best—but it’s

always a good entry point into more detailed subjects and can often spur a good

discussion.

9. What writers other than crime writers do you read?

Aside from crime writers I read mostly non-fiction. Steven

Johnson, Richard Feynman, David McCullough, and Cornelius Ryan are favorites of

mine. Nicholas Pileggi and Peter Maas are favorites on the crime side.

10. Can beautiful writing make up for an average story? Can

a great story make up for dull prose?

I would much rather read an okay story that’s beautifully

written. Let’s face it, The Big Sleep

has story issues, as does The Long

Good-Bye. They’re both so beautifully written no one cares. James Ellroy’s

plots are sometimes indecipherable, but the writing holds me like few others,

though not even I would describe it as beautiful. A great story can make up for dull prose, but it had

better be a great story. I have in

mind a writer who’s sold millions of books that I read strictly because the

stories are so good, even though I find the writing ordinary. He’s the

exception. I’m far more forgiving of a well-written book with a lesser story.

Of course, when both come together—James Lee Burke, for instance, or Dennis

Lehane—that’s when life is good.

Thanks for the visit, Dana. And best of luck with the new book.

Thanks for the visit, Dana. And best of luck with the new book.

Friday's Forgotten Books, April 28, 2017

You can find the links right here.

Stay tuned here for an interview with Dana King coming up at 10:00 AM

Monday, April 24, 2017

Sunday, April 23, 2017

And the Ellery Queen Award goes to

Ellery Queen Award winners include Janet Rudolph, Charles Ardai, Joe Meyers, Barbara Peters and Robert Rosenwald, Brian Skupin and Kate Stine, Carolyn Marino, Ed Gorman, Janet Hutchings, Cathleen Jordan, Douglas G. Greene, Susanne Kirk, Sara Ann Freed, Hiroshi Hayakawa, Jacques Barzun, Martin Greenburg, Otto Penzler, Richard Levinson, William Link, Ruth Cavin, and Emma Lathen.

The Ellery Queen Award was established in 1983 to honor “outstanding writing teams and outstanding people in the mystery-publishing industry

Saturday, April 22, 2017

Friday, April 21, 2017

Friday's Forgotten Books, Friday, April 21,2017

BAD INTENTIONS, Karin Fossum

Norway’s Inspector Konrad Sejer takes a backseat in this story, being almost incidental to the action.

A inmate at a psychiatric hospital, supposedly making a recovery, is allowed a weekend pass to spend time with two old friends. He ends up at the bottom of the lake, exactly why and how is mysterious. His death mimics an earlier one by an immigrant the threesome became involved with. This is a strange little tale, reminding me almost of Hitchcock's ROPE. It's about power, guilt, mothers, and loneliness. Well worth reading if you don't mind ambiguity.

Sergio Angelini, ANGEL'S FLIGHT, Lou Cameron

Yvette Banek, THE MAN WHO WAS NOT, John Russell Fearn

Joe Barone, DEATH AT THE PRESIDENT'S LODGING, Michael Innes

Les Blatt, THE ECHOING STRANGERS, Gladys Mitchell

Bill Crider, DILLINGER, Harry Patterson

Scott Cupp, KONGO, THE GORILLA MAN, Frank Orndorff

Martin Edwards, BIRD IN A CAGE, Frederic Dard

Richard Horton, THE FORTUNE HUNTER, Louis Joseph Vance

Jerry House, EXILES OF TIME, Nelson Bond

George Kelley, THE BEST OF GORDON R. DICKSON, Hank Davis

Margot Kinberg, A JAR FULL OF ANGELS, Babs Horton

Rob Kitchin, THE LONG FIRM, Jake Arnott; SECRET SPEECH, Tom Robb Smith

B.V. Lawson

Evan Lewis, SLEEP WITH THE DEVIl, WAKE UP TO MURDER, JOY HOUSE, Day Keen

Steve Lewis, MURDER BEACH, Bridget McKenna

Brian Lindenmuth, RED RUNS THE RIVER, Lewis Patten

Todd Mason, 100 Best Books Books and Lists

J.F. Norris, THE REEK OF RED HERRINGS, Catriona McPherson

Neer, WE HAVE ALWAYS LIVED IN THE CASTLE, Shirley Jackson; DEATH AND THE PLEASANT VOICES, Mary Fitt

Stephen Nester (THE RAP SHEET) DURANGO STREET, Frank Bonham

Matt Paust, THE AX, Donald Westlake

James Reasoner, RAWHIDE CREEK, L. P. Holmes

Richard Robinson, JEOPARDY IS MY JOB, Stephen Marlowe

Gerard Saylor, GONE GIRL, Gillian Flynn

Kevin Tipple, THE OUTCAST DEAD, Elly Griffiths

TomCat, THE MYSTERY OF THE DEATH TRAP MINE, Three Investigators

TracyK, BURGLARS CAN'T BE CHOSERS, Lawrence Block

Westlake Review, BREAKOUT, Richard Stark

Zybahn, THE HORROR ON THE ASTEROID, Edmond Hamilton

Thursday, April 20, 2017

And the Winners Are: Stuart Woods, Rebecca Pawell and Jonathan King

In 1982, Stuart Woods won the Best First Novel Edgar for CHIEFS. In 2004, Rebecca Pawell won the Best First Novel Edgar for DEATH OF A NATIONALIST. In 2003, Jonathan King won the Best First Novel Edgar for THE BLUE EDGE OF MIDNIGHT.

Megan's Office Bookshelves

For those who wonder, the figurines are carnival prizes made of chalkware and painted by the lucky winners. Her Dad shares her enthusiasm. Both have many examples.

Wednesday, April 19, 2017

Tuesday, April 18, 2017

And the Wiinner is: Daniel Stashower

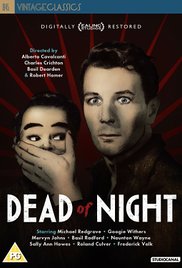

Forgotten Movie: DEAD OF NIGHT

A 1945 film that is basically an anthology of four horror/ghost stories bound together by the idea that an architect has been dreaming each of them in a continuous nightmare. The stories vary in quality-two I liked, one was more humorous than scary and one didn't work for me. And pulling them into one story at the end seemed odd too. Four writers, four directors and although we finished it, I wouldn't recommend it. The only familiar face was Michael Redgrave's. Apparently during the war, the British studios were not permitted to make horror movies and this was an early attempt to renew making them.I am sure this film has its fans based on the ratings, but we were not among them.

Monday, April 17, 2017

And the 2014 Raven Award goes to Aunt Agatha's Bookstore in Ann Arbor

|

| Jamie and Robin Agnew |

Sunday, April 16, 2017

Saturday, April 15, 2017

And the Winner is: Stephen Gaghan #Edgarmemories #edgars2017

In 2006 SYRIANA, by Stephen Gaghan, won the Edgar for best screenplay

(From David Ansen at NEWSWEEK:

There were more than

a few moments in the complex, fascinating "Syriana"--writer-director

Stephen Gaghan's globe-hopping sociopolitical thriller about the oil

industry--when I was confused, not quite sure who was plotting to do

what to whom, or why. There's a method to this murkiness, it turns out.

Like the myriad schemers in the movie--oil-rich Arab princes, Texas

entrepreneurs, CIA operatives, Islamic fundamentalists, Washington

lawyers, Justice Department investigators--Gaghan uses misdirection to

achieve his goals. He takes us into a world that's built on moral

quicksand, where the good guys act like bad guys and the bad like good,

and everyone has perfectly good reasons to do the terrible things they

do. And when the pieces come together and clarity is finally restored,

what you discover can make your hair curl.

As he did in his Oscar-winning screenplay for "Traffic," Gaghan shuffles multiple stories, often continents apart, only gradually unveiling how they're connected. There's an Arabic-speaking CIA agent left out in the cold by his handlers in Washington, played by a bearded, heavyset, deglamorized George Clooney. There's an ambitious Washington lawyer (Jeffrey Wright) investigating a questionable merger between two Texas oil firms--that want drilling rights in Kazakhstan, and the powerful boss of the law firm (Christopher Plummer), who insinuates himself in the power struggle between two heirs vying to become the emir of a Persian Gulf country. One of those princes (Alexander Siddig, an actor to watch) has given his country's drilling rights to the Chinese, which makes him an official enemy of the U.S. government. Yet his new adviser (Matt Damon) is an American oil consultant, based in Geneva, who's parlayed the tragic death of his son at the emir's Spanish home into an economic opportunity. At the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder is an unemployed Pakistani migrant oil worker (Mazhar Munir) who's taken under the wing of a radical Islamic mentor.

The movie is partly (and loosely) based on the exploits of CIA agent and author Robert Baer, the model for Clooney's character. Gaghan did massive research before writing, and you can feel it in the dense, information-packed texture. In its suspenseful two hours, "Syriana" packs in enough material for two movies. Sometimes you wish Gaghan would simply slow down and let us linger awhile with his characters. What we get instead are merely tantalizing glimpses of their fraught home lives: Clooney's unhappy son, tired of being shuffled around the world; Wright's alcoholic father, who keeps showing up on his doorstep.

Gaghan's movie doesn't play by conventional Hollywood action-movie rules (when it tries to, in one action scene near the end, it can sacrifice sense for sensation). This is a movie that sticks its political neck out, that throbs with dread, paranoia and outrage, that doesn't coddle the audience by neatly tying things up. "Syriana" demands both an alert mind and a stout heart, and not just for its powerfully unpleasant torture scene. Its dark, dog-eat-dog vision of the world we live in may give you geopolitical nightmares.

As he did in his Oscar-winning screenplay for "Traffic," Gaghan shuffles multiple stories, often continents apart, only gradually unveiling how they're connected. There's an Arabic-speaking CIA agent left out in the cold by his handlers in Washington, played by a bearded, heavyset, deglamorized George Clooney. There's an ambitious Washington lawyer (Jeffrey Wright) investigating a questionable merger between two Texas oil firms--that want drilling rights in Kazakhstan, and the powerful boss of the law firm (Christopher Plummer), who insinuates himself in the power struggle between two heirs vying to become the emir of a Persian Gulf country. One of those princes (Alexander Siddig, an actor to watch) has given his country's drilling rights to the Chinese, which makes him an official enemy of the U.S. government. Yet his new adviser (Matt Damon) is an American oil consultant, based in Geneva, who's parlayed the tragic death of his son at the emir's Spanish home into an economic opportunity. At the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder is an unemployed Pakistani migrant oil worker (Mazhar Munir) who's taken under the wing of a radical Islamic mentor.

The movie is partly (and loosely) based on the exploits of CIA agent and author Robert Baer, the model for Clooney's character. Gaghan did massive research before writing, and you can feel it in the dense, information-packed texture. In its suspenseful two hours, "Syriana" packs in enough material for two movies. Sometimes you wish Gaghan would simply slow down and let us linger awhile with his characters. What we get instead are merely tantalizing glimpses of their fraught home lives: Clooney's unhappy son, tired of being shuffled around the world; Wright's alcoholic father, who keeps showing up on his doorstep.

Gaghan's movie doesn't play by conventional Hollywood action-movie rules (when it tries to, in one action scene near the end, it can sacrifice sense for sensation). This is a movie that sticks its political neck out, that throbs with dread, paranoia and outrage, that doesn't coddle the audience by neatly tying things up. "Syriana" demands both an alert mind and a stout heart, and not just for its powerfully unpleasant torture scene. Its dark, dog-eat-dog vision of the world we live in may give you geopolitical nightmares.

Friday, April 14, 2017

And the Winner Is: Ed McBain #Edgarmemories #edgars2017

Ed McBain is awarded the Grand Master Award for lifetime achievement

(From the New York Times Time Machine)

Published: May 13, 1986

''The Suspect'' by L. R. Wright (Viking Penguin) has

been named the best novel of 1985 by the Mystery Writers of America.

The award for best critical/ biographical work went

to ''John Le Carre'' by Peter Lewis (Frederick Ungar). Ed McBain

received the grand master award for lifetime achievement.

Among other winners of the organization's Edgar

Allan Poe Awards, presented at the Sheraton Centre in New York on

Friday, were ''When the Bough Breaks'' by Jonathan Kellerman (Atheneum),

best first novel; ''Pigs Get Fat'' by Warren Murphy (NAL), best

paperback original; ''Savage Grace'' by Natalie Robins and Steven M. L.

Aronson (William Morrow), best fact crime, and ''The Sandman's Eyes'' by

Patricia Windsor (Delacorte), best juvenile novel.

Friday's Forgotten Books, April 14, 2017: Smalltown Cops and Sheriffs Day

Certainly one of the finest first crime novels ever, you will swear you have been around Cork O'Connor long before this 1998 debut. Cork is the former sheriff of Aurora, MN and lost his job and his family after a meltdown on the job. He is trying to win them back, despite his relationship with another woman, when a judge dies and a boy disappears. His former wife has hooked up with a newly elected Senator which complicates things more than a little. This is such a skilled outing and Krueger is more than adept at weaving a crime story with a family story. His characters have grit, his setting has atmosphere and his plot is always credible yet surprising. Coming off of ORDINARY GRACE, which I loved last year, this is a terrific piece of writing. You cannot not admire everything about this book.

Yvette Banek, ONE WAS A SOLDIER, Julie Spencer-Fleming

M.W. Cunningham, DEATH OF A WITCH, M.C. Beaton

David Cranmer, THE COLD DISH, Craig Johnson

Curt Evans, A MAMMOTH MURDER, Bill Crider

Jerry House, DEATH OF A GLUTTON, M.C. Beaton

George Kelley, THE PLEASANT GROVE MURDERS, Jack Vance

B.V. Lawson, UNDER THE SNOW, Kerstin Ekman

Todd Mason, Bill Pronzini: "The Hanging Man"; Howard Rigsby: "Dead Man's Story"; James Shaeffer, "The Long Arm of the Law"

J.F. Norris, LAST SEEN WEARING, Hillary Waugh

Matthew Paust, CURSED TO DEATH, Bill Crider

Petrona, BLUE HEAVEN, C.J. Box

James Reasoner, THE CLUE OF THE RUNAWAY BRIDE, THE CLUE OF HUNGRY HORSE, Erle Stanley Gardner

Katherine Tomlinson, A GREAT RECKONING, Louise Penney

TracyK, DEATH ON THE MOVE, Bill Crider

Mark Baker, G IS FOR GUMSHOE, Sue Grafton

Joe Barone, THE SPIRAL STAIRCASE, MY CLIMB OUT OF DARKNESS, Karen Armstrong

Brian Busby, SHADOW ON THE HEARTH, Judith Merril

Bill Crider, THE DAME'S THE GAME, Al Fray

Martin Edwards, THE MARTINEAU MURDERS, Richard Hull

Richard Horton, The HEROD Men, by Nick Kamin/Dark Planet, by John Rackham

Margot Kinberg, SOMETHING IN THE AIR, John Alexander Graham

Rob Kitchin, BULLDOG DRUMMOND, Sapper

J.F. Norris, A BEASTLY BUSINESS, John Blackburn

Steve Lewis, SLEEP WITH SLANDER, Dolores Hitchens

Reactions to Reading, BLOWBACK, Bill Pronzini

Richard Robinson, WILDERNESS DAYS, Sigurd Olson

Kevin Tipple/Barry Ergang, "Don Diavolo Mysteries" by Clayton Rawson

TomCat, SHE SHALL DIE, Anthony GIlbert

Thursday, April 13, 2017

And the Winner is: S.J. Rozan #Edgarmemories #edgars2017

In 2002, WINTER AND NIGHT by S.J. Rozan won the Edgar for Best Novel.

From Booklist

*Starred Review* Lydia Chin and Bill Smith remain one

of the very best private-eye duos in the genre, and this installment of

Rozan's highly readable and most entertaining series lives up to the

superlatives we have heaped upon its predecessors. When Bill receives a

call from the New York City police telling him that his teenage nephew,

Gary, is in jail and has asked for him, Bill is certainly surprised,

especially because he has had no contact with his sister, Gary's mother,

in some time. When he manages to get Gary released into his custody,

the boy will not say why he has come to New York, only that he has

something important to do. Bill insists that Gary must call his mother,

but Gary, a football player, smashes out a window, drops two stories

into the alley, and runs away again. Thus begins a truly tangled tale

that leads Bill and Lydia into the world of Gary's hometown, a New

Jersey suburb, where high-school football rules the community--and may

have led to the murder of a young girl by a team member who just might

be Gary. The course of events also forces Bill to reveal to Lydia the

truth about his own troubled past and why he so desperately needs to

find and help Gary. As before, Rozan delivers strong characters, deft

plotting, and a hard-driving narrative. We'll say it again: don't miss

this one. Stuart Miller

And the Winner is: Naomi Hirahara #Edgarmemories #edgars2017

|

| Naomi on the right |

In 2007 SNAKESKIN SHAMISEN by Naomi Hirahara won the Edgar for Best Paperback Original.

KIRKUS REVIEW

Mas Arai’s probe of a restaurant murder stretches back 50 years to old secrets.

Elderly gardener Mas Arai (Gasa-Gasa Girl, 2005, etc.) attends a party for lawyer friend George “G.I.” Hasuike at Mahalo, a Hawaiian restaurant in Torrance. Randy Yamashiro, who’s throwing the bash, calls G.I. his good-luck charm after winning half-a-million dollars on a Spam slot machine during the pair’s recent trip to Vegas. Curmudgeonly Mas is pleased to meet Juanita Gushiken, G.I.’s fiancée, but takes an instant dislike to brash Randy and leaves the party early, just after G.I. and Randy get into an alcohol-fueled fight that threatens to end their friendship. An oblique message from Juanita brings Mas back to Mahalo, where Randy’s been murdered. For obvious reasons, G.I. is the prime suspect. So reluctant Mas is drawn again into a murder investigation. At least this time he has a partner—assertive Juanita insists on helping to find the killer—and a big clue: the unique three-stringed instrument of the title found near the body. Mas’s collaboration with Juanita sparks some amusing friction. It’s easy to trace the shamisen to distinguished attendee Judge Parker, but not so easy to link him to the murder. The answer lies in a crime from the ’50s and some painful postwar memories.

Hirahara’s complex and compassionate portrait of a contemporary American subculture enhances her mystery, and vice versa.

Elderly gardener Mas Arai (Gasa-Gasa Girl, 2005, etc.) attends a party for lawyer friend George “G.I.” Hasuike at Mahalo, a Hawaiian restaurant in Torrance. Randy Yamashiro, who’s throwing the bash, calls G.I. his good-luck charm after winning half-a-million dollars on a Spam slot machine during the pair’s recent trip to Vegas. Curmudgeonly Mas is pleased to meet Juanita Gushiken, G.I.’s fiancée, but takes an instant dislike to brash Randy and leaves the party early, just after G.I. and Randy get into an alcohol-fueled fight that threatens to end their friendship. An oblique message from Juanita brings Mas back to Mahalo, where Randy’s been murdered. For obvious reasons, G.I. is the prime suspect. So reluctant Mas is drawn again into a murder investigation. At least this time he has a partner—assertive Juanita insists on helping to find the killer—and a big clue: the unique three-stringed instrument of the title found near the body. Mas’s collaboration with Juanita sparks some amusing friction. It’s easy to trace the shamisen to distinguished attendee Judge Parker, but not so easy to link him to the murder. The answer lies in a crime from the ’50s and some painful postwar memories.

Hirahara’s complex and compassionate portrait of a contemporary American subculture enhances her mystery, and vice versa.

Wednesday, April 12, 2017

And the Winner is: Martin Edwards #Edgarmemories #edgars2017

In 2016, THE GOLDEN AGE OF MURDER, Martin Edwards,

Edgar for Best Critical/Biographical

Edgar for Best Critical/Biographical

|

| Martin Edwards on right |

Review: THE GOLDEN AGE OF MURDER by Martin Edwards“Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?” demanded Edmund Wilson in a New Yorker essay published in 1945. Taking its title from Agatha Christie’s Who Killed Roger Ackroyd? (1926), the essay describes the detective novel as ‘sub-literary’, a perhaps understandable addiction that ranked somewhere between crossword puzzles and smoking. Only a year earlier, however, John Strachey, writing in The Saturday Review, had declared that readers were living through ‘the Golden Age of English Detection’, describing detective fiction as ‘masterpieces of distraction and escape.’ So popular and pervasive were Golden Age mystery novels that Bertolt Brecht – tongue firmly wedged in cheek, no doubt – could claim that, “The crime novel, like the world itself, is ruled by the English.” The contradictions persist to this day. The Guinness Book of Records claims that Agatha Christie, with sales in excess of two billion, is second only to The Bible and William Shakespeare in terms of books sold. And yet the perception remains that Golden Age mystery novels were no more than bland exercises in puzzle-solving, comfort blankets for a middle class readership all too eager to be persuaded that while the country house defences might be breached, and the village green become stained with blood, such anomalies would be detected by ‘the little grey cells’ of superior education and the status quo quickly restored. “The received wisdom is that Golden Age fiction set out to reassure readers by showing order restored to society, and plenty of orthodox novels did just that,” writes Martin Edwards in the opening chapter of The Golden Age of Murder. Yet the best of the Golden Age writers, he argues, and particularly those members of the Detection Club who account for the book’s subtitle, ‘The Mystery of the Writers Who Invented the Modern Detective Story’, defied stereotypes and were ‘obsessive risk-takers’ as they reimagined the possibilities and potential of the crime novel. “Violent death is at the heart of a novel about murder,” writes Edwards, “but Golden Age writers, and their readers, had no wish or need to wallow in gore … The bloodless game-playing of post-conflict detective stories is often derided by thoughtless commentators who forget that after so much slaughter on the field of battle the survivors were in need of a change.” Edwards, an award-winning detective novelist and the Archivist of the Detection Club, has written a fabulously detailed book that serves a number of purposes. A rebuttal of the ‘perceived wisdom’ that Golden Age mystery fiction was trite and clichéd is to the forefront, but The Golden Age of Murder also functions as a history of the Detection Club, which was formed in 1930 and over the years included in its membership Christie, Sayers, Berkeley, G.K. Chesterton, Freeman Wills Croft, Ronald Knox, A.A. Milne, Baroness Orczy, Helen Simpson, Hugh Walpole, Gladys Mitchell, Margery Allingham, John Dickson Carr, Nicholas Blake, Edmund Crispin and Christianna Brand, among many others. Through this framework Edwards weaves a mind-boggling number of plot summaries of novels (without, naturally, ever giving away the all-important crucial twists), the authors’ fascination with real-life crimes, and the way in which the Golden Age mysteries reflected the turbulent decades of the 1920s and 1930s and on into the Second World War, persuasively arguing that, “The cliché that detective novelists routinely ignored social and economic realities is a myth.” Equally fascinating is his documenting of the frequently tortured private lives of the authors, with Edwards turning detective himself as he explores how alcoholism, unacknowledged children, repressed homosexuality, unrequited passion, radical political activism and self-loathing – to mention just a few examples – found their way into the writers’ novels. There are also a number of intriguing digressions, such as when Edwards notes the relationship between detective fiction and poetry. T.S. Eliot, Dylan Thomas, W.H. Auden, Cecil Day-Lewis (who published his crime novels under the pseudonym Nicholas Blake) and Sophie Hannah are among those name-checked as critics or authors: “From [Edgar Allan] Poe onwards, a strikingly high proportion of detective novelists have also been poets,” says Edwards. “They are drawn to each form by its structural challenges.” As a novelist himself, Edwards can be cynically humorous about the publishing industry (“Allen [Lane] met Christie when she called at the office to complain about the dustjacket of The Murder on the Links, having failed to realize that when a publisher asks an author’s opinion of a jacket, the response required is rapture.”) and his quirky style is reflected in his chapter headings (Chapter 15 is titled ‘Murder, Transvestism and Suicide during a Trapeze Act’). For the most part, however, Edwards plays a straight bat with a sustained and impassioned celebration of the Golden Age mystery novel. The Golden Age of Murder is as entertaining as it is a comprehensively researched work, and one that should prove essential reading for any serious student of the crime / mystery novel. ~ Declan Burke This review was first published in the Irish Times. |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)